Arthur Wellard

(1902-1980) was a "Tour de Force of the Cricket world" in England. He played for Somerset, England and the Gaieties. He spent his final playing years keeping an avuncular eye on a wandering team of "keen but erratic Home Counties amateurs" called the Gaieties CC, founded 1937. He was its coach, critic, confessor and counsellor, and his advice was based on decades of survival in the upper echelons of first class cricket.

Guardian

article "Sixer of the Century"

A Tribute to Arthur Wellard

Harold Pinter

In July 1974 Gaieties C.C. was engaged in an excruciatingly tense contest with Banstead. We had bowled Banstead out for 175 and had not regarded the task ahead as particularly daunting. However, we had made a terrible mess of it and when our ninth wicket fell still needed five runs to win. That we were so close was entirely due to our opening batsman, Robert East, who at that point was ninety-six not out. The light was appalling. Our last man was Arthur Wellard, then aged seventy-two. He wasn't at all happy about the reigning state of affairs. He had castigated us throughout the innings for our wretched performance and now objected strongly to the fact that he was compelled to bat. I can't see the bloody wicket from here, how do you expect me to see the bloody ball? As a rider, his rheumatism was killing him. (He had bowled eighteen overs for twenty-nine runs in the Banstead innings). He lumbered out to the wicket, cursing.

Banstead were never a sentimental crowd. The sight of an old man taking guard in no way softened their intent. Their quickie had two balls left to complete the over. He bowled them, they were pretty quick, and Arthur let both go by outside the off-stump, his bat raised high. Whether he let them go, or whether he didn't see them, was a question o( some debate, but something told us that he had seen them, clearly, and allowed them to pass

East drove the first ball of the next over straight for four, bringing up his hundred and leaving us with one run to win. The next five balls he struck to the deep-set field. There were clear singles for the asking in these shots but Arthur in each case declined the invitation, with an uplifted hand. He was past the age, his hand asserted, when running singles was anything else but a mug's game.

So Arthur prepared to face what we knew had to be the last over, with one run to win. The Gaieties side, to a man, stood, smoked, walked in circles outside the pavilion, peering out at the pitch through the gloom. It appeared to be night, but we could discern Arthur standing erect, waiting for the ball. The quickie raced in and bowled. We saw Arthur's left leg go down the wicket, the bat sweep, and were suddenly aware that the ball had gone miles in the long-on area, over the boundary for four. We had won.

In the bar he pronounced himself well pleased. No trouble, he said. He tried to get me with a yorker. Where's the boy who made the ton? He did well. Tell him he can buy me a pint.

Arthur played his last game for Gaieties in 1975. By this time his arm was low and discernibly crooked and his bowling was accompanied by a remarkable range of grunts. He was also, naturally, slow, but his variation of length still asked questions of the batsman and he could still move one away, late. But he could now be hit and he could no longer see the ball quickly enough to catch it. He retired from the field at the age of seventy-three and became our umpire. He bad been playing cricket for some fifty years.

What was Hammond like, Arthur, in his prime? Hammond? I used to bowl against Hammond at Taunton. Jack White set two rings on the off-side, an inner ring and ~an outer ring. Old Wally banged them through both rings. Off the back foot. Nobody could stop him. Never anyone to touch old WaIly on the offside, off the back foot. What was he like on the front foot, Arthur? He was bloody useful on the front foot, too.

What about Larwood, Arthur? How fast was he? Larwood? He was a bit quick, Larwood. Quickest thing I ever saw. First time I faced him was at Trent Bridge, that was my first season with Somerset. Who's this Larwood? I said, supposed to be a bit pacey, is he? I didn't reckon the stories. He's a bit quick, they said. A bit quick? I said. We'll see about that. I'd faced a few quickies in Kent. Well, I went out there and I got four balls from Larwood and I didn't see any of them. The first I knew about them was Ben Lilley throwing them back. The fifth ball knocked my hob over and I didn't see that one either. I'll tell you, he was a bit quick, Harold Larwood.

Wisden supports this: May 1929. Trent Bridge. Notts v. Somer-set. A. W. Wellard b. Larwood 0. What Arthur didn't mention was that in the Notts innings we read: H. Larwood b. Wellard 0.

Did I ever tell you the story about Harry Smith of Leicester? Arthur went on. He had a stutter. One day they went out into the field against Notts. Harry likes the look of the wicket, he thinks it'll suit him. I'll tell you what, S-s-skip, he says to his skipper, I think I'll b-b-bounce one or two. Wait a minute, says the skip, you know who they've got on the other side? They've got Larwood and Voce. I'll just b-b-bounce one or two, says Harry. So he bounces one or two and Notts don't like it much. Anyway, Leicestershire go in before the end of the day and Larwood and Voce knock them over like tin soldiers and suddenly old Harry finds he's at the wicket. Larwood and Voce go for him. Harry's never seen so many balls around his ears. He thinks they're going to kill him. Suddenly he gets a touch and Sam Staples dives at first slip and it looks as though he's caught it. Harry takes off his gloves and walks. Wait a minute, Harry, says Sam, it was a bump ball, I didn't catch it. Yes, you f-f -f-fucking-well did, says Harry, and he's back in the pavilion before you can say Jack Robinson.

Arthur would roar at that one but he never missed what was going on in the middle. Even side-on to the pitch and not apparently paying any attention he could see what the ball was doing. She popped, he would say, he wasn't forward enough. It's no good half-arsing about, it's no good playing half-cock on a wicket like this, it's not the bloody Oval. What he wants to do, he wants to get his front foot right forward, see what I mean, get to the pitch of it. Then he stands a chance. The batsman was caught at slip. It was inevitable, said Arthur. Inevitable. He was half-arsing about.

Once, on a beautiful wicket at Eastbourne I suddenly played a cover drive for four, probably the best shot I ever played in my life. A few overs later I was clean bowled. Arthur was waiting for me in front of the pavilion. What do you think you're doing? He asked. What do you mean? I said. What do you think you're doing, playing back to a pitched-up ball? Was it pitched-up? I said. I thought it was short of a length. Short of a length! he exploded. You must be going blind. You made it into a Yorker! Oh, I said. Well, anyway, Arthur, what did you think of that cover drive? Never mind the cover drive, Arthur said. Just stop all that playing back to full-length balls. You had a fifty there for the asking. Sorry, Arthur, I said.

Arthur was a stern critic of my batting and with good reason. My skills were limited. There were only two things I could do well. I possessed quite a gritty defence and I could hit straight for six - sometimes, oddly enough, off the back foot. But I didn't do either of these things very often. I had little concentration, patience or, the most important thing of all, true relaxation. And my judgement was distinctly less than impeccable. Listen, son, Arthur would say, you've got a good pair of forearms but just because you give one ball the charge and get away with it doesn't mean you can go out and give the next ball the charge, does it? Be sensible. What do you think the bowler's doing? He's thinking, son, thinking, he's thinking how to get you out. And if he sees you're going to give him the charge every ball he's got you for breakfast. You're supposed to be an intelligent man. Use your intelligence. Sorry, Arthur, I said.

Occasionally I would perform respectably, under Arthur's scrutiny. Once, when we were in terrible trouble, forty for five or something, against Hook and Southborough, I managed to get my head down and stayed at the wicket for an hour and a quarter, for some twenty-five runs; thus, with ~my partner, warding off disaster, On my return to the pavilion Arthur looked at me steadily and said: I was proud of you. I don't suppose any words said to me have given me greater pleasure.

As it well known, Arthur (until Sobers beat it) held the record for hitting the most sixes in an over; five - off Armstrong of Derbyshire in 1936. He did the same thing in 1938, off Coolly. During his professional career he scored over twelve thousand runs, of which three thousand were in sixes. (He also took over sixteen hundred wickets) He agreed that he was seeing the ball well against Armstrong and Coolly but the six he remembered above all was one he hit off Amar Singh at Bombay on Lord Tennyson's Indian tour of 1938.

He wasn't a bad bowler, Amar Singh. He moved it about a bit. He dug it in. You had to watch yourself. Anyway, he suddenly let one go, it was well up and swinging. I could see it all the way and I hit it. Well, they've got these stands in Bombay, one on top of the other, and I saw this ball, she was still climbing when she hit the top of the top stand. I was aiming for that river they've got over there. The Ganges. If it hadn't been for that bloody top stand I'd have had it in the Ganges. That wasn't a bad blow, that one.

To do with the same tour, Arthur told us the story about Joe Hardstaff and the Maharajah, the night before the game at Madras. This Maharajah was a big drinker, you see, so he invited a few of us over for a drinking competition one night. Well, I was there and old George Pope and one or two others, but we couldn't take the pace, so we dropped out, round about midnight. Well, this Maharajah, he had everything on the table: whisky, brandy, gin, the lot, and it was left to him and Joe, and Joe had to go with him, glass for glass. Well, Joe went with him, Joe could take a few in those days, and they went at it until five o'clock in the morning and the Maharajah is still standing and Joe suddenly goes out like a light. Amazing man, that Maharajah, can't remember his name. Anyway, we take Joe home, get him into his bed, he's still not uttering, he's as good as dead, and, my word of honour, we think, Christ, old Joe's gone too far this time. Next day he goes out to bat before lunch, he stays there all day and he makes two hundred. Sweated it all out, you see.

Wisden confirms the innings, at least: Lord Tennyson's Team v. Madras. January 1938. J. Hardstaff c. Gopalan b. Parthasarathi. 213. (Hardstaff never appeared in trouble, according to Wisden, and, batting five hours, he hit twenty-four fours.)

As an umpire, Arthur was strictly impartial, by the highest standards, but didn't see the giving of advice to his side as straying from the moral obligations his role imposed. The batsman would grope forward, snick a single through the slips, run, and find Arthur staring at him at the bowler's end. Where's your feet? Arthur would say out of the side of his mouth. You've got feet, haven't you? Use them. You're playing cricket, son, not poker. To our off-break bowler he would mutter: Go round the wicket and bring up another short leg, put him round the corner, give it some air, make the most of it, she's turning, son, she's turning. Or, to me, the captain of the day: What are you doing with a silly mid-off on a wicket like this? Put him out to extra cover. Let the lad have a go. See what I mean? Pretend you're frightened of him. He'll fall for it.

Once, when I was the silly mid-off in question, having declined his advice, I dived and made a catch. As the batsman was retreating, Arthur called me over. Good catch, he said. Except it wasn't a catch. It was a bump ball. Bump ball? I said. It was a clean catch. Cunning bugger, said Arthur. That was a bump ball. The trouble was the man walked. If he'd have stayed where he was and you'd have appealed I'd have given him not out. Anyway, he's out, I said. He's out all right, said Arthur. But I didn't give him out.

He umpired for Gaieties for four years He never gave a Gaieties batsman not out when he thought him to be out. Nor did he ever give opposition batsmen out when he considered them to be not out. No chance, he would retort to our lbw appeals, not in the same parish, you must be joking.

Compton and Edrich? On a hiding to nothing, son. Never known anything like it. What year was it, after the war, at Lords, we got rid of Robertson, we got rid of Brown, and then those two buggers came together and they must have made something like a thousand. I'd been bowling all bloody day and the skipper comes up to me and he says, Go on, Arthur, have one more go. One more go? I said. I haven't got any legs left. One more go, says the skip, go on, Arthur, just one more go. Well, I had one more go and then I dropped dead.

Wisden reports: May. 1948. Lords. Middlesex: Robertson c. Hazell b. Buse 21. Brown c. Mitchell-Innes b. Buse 31. Edrich not out 168. Compton not out 252. Middlesex declared at 478 for 2 fifty minutes before the close of play on the first day. Wellard's analysis; Overs 39. Maidens 4. Runs 158. Wickets 0.

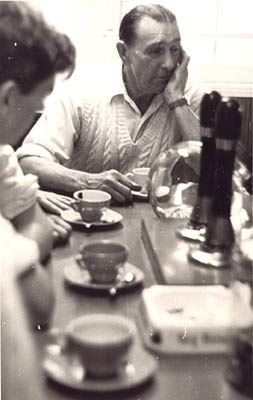

He moved to Eastboume with his wife in 1977. Once, finding myself in the area, I rang him and arranged to meet him for a drink. I walked into the pub. It was empty, apart from a lone big man, erect at the bar. He was precisely dressed, as always: tweed jacket, shirt and tie, grey flannels, shoes well polished. He passed a glass to me: the glass, like the ball, tiny in his hands. No, he didn't bother much about club cricket in the Eastboume area. Anyway, his legs were bad. All the old stagers were dropping like flies. Harold Gimblett had topped himself. He was always a nervous kind of man, highly strung. Remember his first knock for Somerset? Made a hundred in just over the hour. He did it with my bat. I lent it to him, you see. He was only a lad.

Yes, he watched a bit of the game on television. Viv Richards was world class. Mind you, Bradman would take a lot of beating, when you came down to it. But Hobbs was probably the best of the lot.

Arthur played for England against Australia in 1938. He took 2 for 96 and 1 for 30, scored 4 and 38 (including a six into the Grandstand). He gave me his English cap and the stump he knocked over when he bowled Badcock.